Our History

Founded around 1099 by Alfune, then Bishop of London, St Giles’ has been home to every type of person imaginable: tanners, brewers, crooks, rebels, voyagers, thespians, and even royalty. Funded initially by the guilds and people of its parish, it grew along with them out of swampy moorlands into prosperity, as a spiritual centre, with a strong musical and artistic heritage, and, at times, as a crucible for religious and political upheaval.

Notable historical worshippers include Bishop Lancelot Andrewes, who translated the King James Bible; the navigators Frobisher and Gilbert; the composer and organist Thomas Morley; mapmaker John Speed; and playwrights Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare. The great poet John Milton was buried here, and reformer Oliver Cromwell was married here. Author Daniel Defoe was baptised here, and the grandfather of John and Charles Wesley, who founded Methodism, was vicar here.

Our church has persisted through plague, fire, and bombings and has served as a sanctuary for the poor, the sick and the homeless — giving back to the people who have been its lifeblood for nearly a millennium.

We have included below the text of a history of the church, written in the 1980’s by churchwarden JH Holroyd.

We have also included two links, to a pdf of the original typed copy of that history, and to a much lengthier 1888 history written by churchwarden John James Baddeley.

A HISTORY AND GUIDE OF ST. GILES WITHOUT CRIPPLEGATE

Written in the 1980s by Churchwarden JH Holroyd Esq.

THE EARLY CHURCH

It is thought that a small chantry chapel existed on the site of St. Giles in Saxon times, as John Stow—the famous Elizabethan historian of London—tells us in his survey published in 1598, that the body of King Edmund the Martyr rested at Cripplegate in 1010 after his death at the hands of the Danes. It is unlikely that the body of a King would have remained overnight unless in a chapel.

Stow also records that Alfune who later helped Rahere build the neighbouring church of St. Bartholomew the Great, and became its first Hospitaler, built a church by Cripplegate about 1099.

Cripplegate was the oldest City gate and the word ‘Crepelgate'—of Anglo-Saxon origin—means a covered way presumably to the Barbican watch tower. Queen Elizabeth I passed through it on her accession in 1558. It was partly destroyed during the Commonwealth, repaired after the Restoration, and finally demolished in 1760 after the City Lands Committee had accepted a tender for £91 from a carpenter of Coleman Street to remove it. A blue plaque on Roman House in Wood Street shows its site.

ST. GILES IN THE MIDDLE AGES

In 1295 the living of St. Giles was set aside for the newly created office of Sub Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral, and its Dean and Chapter have been the patrons ever since.

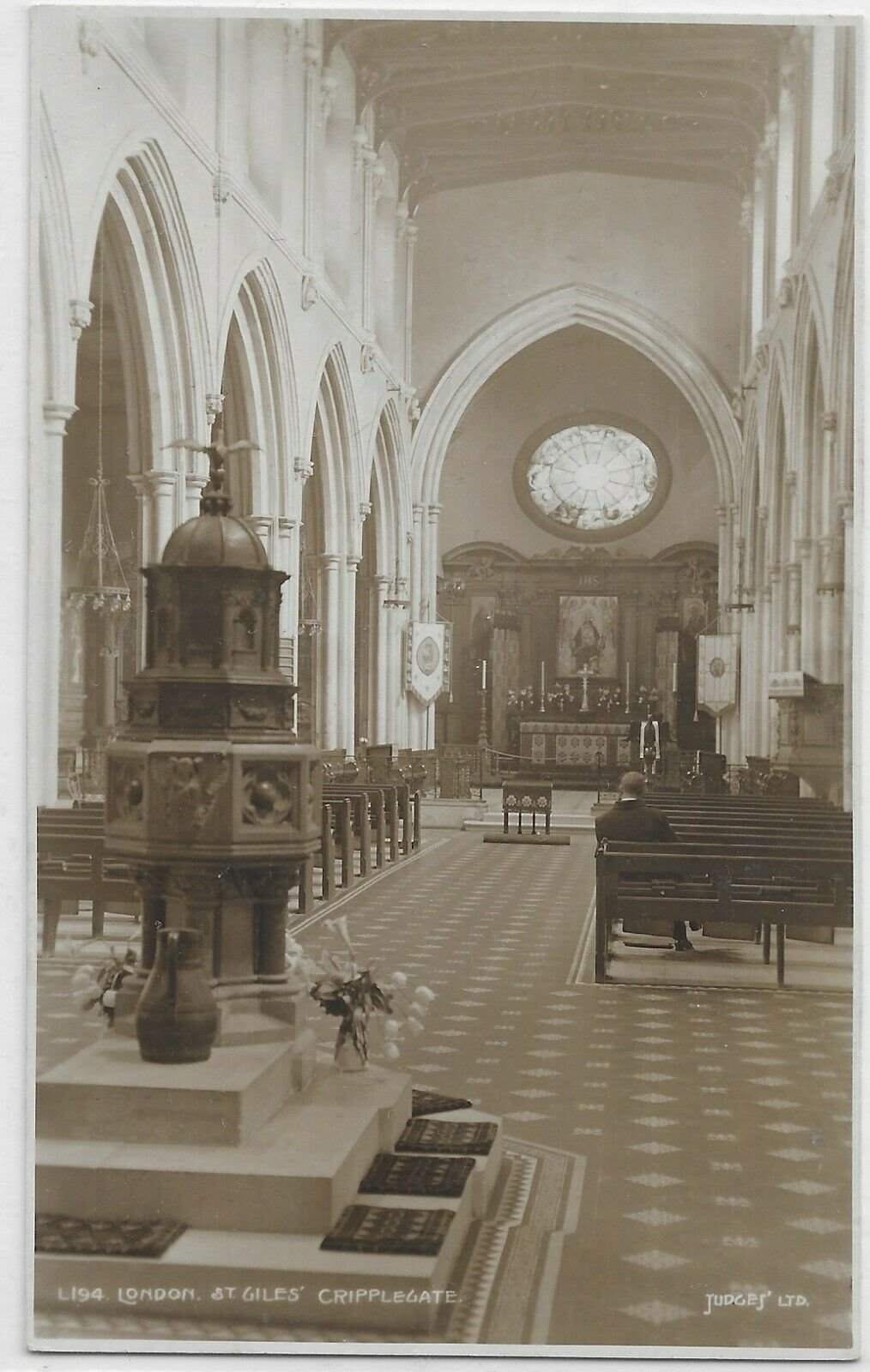

The Norman church stood for almost three hundred years before being re-built in the Gothic perpendicular style in 1390 to accommodate the increasing population of the parish. The pillars of the nave still stand today. Other visible reminders of the re-building at the end of the 14th century are the two small arched doors in the south aisle which must have opened on to spiral staircases leading to the rood screen, long since vanished, which separated the chancel from the body of the church, and from which priests occasionally conducted services. Also surviving after nearly 600 years are the medieval sedilia and piscina set into the south wall at the eastern end of the chancel by the high altar.

The rebuilding of 1390 was financed largely by the various guilds attached to St. Giles who were the forerunners of the City Livery companies. The Guilds were benevolent societies, and providing a decent Christian burial for their members was one of their most important functions. Each Guild adapted a patron saint and had their own chapel within the church.

The oldest known guild associated with St. Giles was that of St. Mary and St. Giles founded by Queen Maud, the wife of Henry I (1100 - 1135). The number of Guilds increased during the Middle Ages with the founding of the Guild of St. Mary in 1348, St. John 1361, St. George 1368 and St. Eloy in 1437. They continued to function until the Reformation when, in 1547, they were disendowed and their funds appropriated for purely secular purposes.

In the 14th century St. Giles was one of four churches appointed to ring the curfew the others being: St. Mary-le-Bow, St. Bride's and All Hallows-by- the-Tower.

The medieval church had a chancel twice the present length, and the carved corbels depicting musicians supporting the clerestory shafts are all that remain of the original chancel.

THE REFORMATION AND THE ELIZABETHAN AGE

One of the great figures in England at the time of the Reformation was Sir Thomas More, Lord Chancellor from 1529 to 1532, who was born in the parish at Milk Street on 2nd February 1477. He was the second son of an alderman and a King's Bench Judge, Sir John More, who was married in St. Giles on 24th April 1474. As a child, Sir Thomas More would have worshipped in the church with his family.

A disastrous fire on 12th September 1545 destroyed the interior of the medieval church. When it was rebuilt, it took on much of its present shape.

During the controversial religious period of the Reformation, one of the Vicars of St. Giles was an extreme Puritan, Robert Crowley, who was ousted from the living in 1566 for refusing to wear a surplice. However, he was re-instated in 1578 and retained the living until his death ten years later.

His successor was St. Giles' most famous vicar, Lancelot Andrewes, the brilliant preacher and scholar and one of the translators of the Authorised Version of the Bible. He held the living from 1588 to 1605 before being appointed Dean of Westminster and then Bishop of Chichester. He was subsequently Bishop of Ely and then of Winchester. He was the last occupant of Winchester House, the town palace of the Bishops of Winchester by the river in Southwark, where he died in 1626. His tomb can be seen today in Southwark Cathedral; and in St. Giles, the fine brass Victorian eagle lectern, which stands on the south side of the chancel steps commemorates him.

At this time the parish was at its most prosperous and housed several famous figures of the Elizabethan age such as John Foxe (1516 - 1587), lecturer at St. Giles, and author of the famous book of Protestant Martyrs, who is buried in the church. Sir Martin Frobisher, the great seaman and artic explorer who endeavoured to find a new route to the East via the North West Passage round the northern coast of what is now Canada. Sir Humphrey Gilbert (1539- 1583), navigator and founder of Newfoundland; Thomas Morley (1557 1603) great musician and organist of St. Giles; John Speed (1552 1629) map maker and historian, buried under the floor near his monument on the south aisle wall (restored by the Merchant Taylors' Livery Company in 1971). Ben Johns on (1573 - 1637) Poet Laureate; Edward Alleyn (1566 1626), famous actor manager and founder of Dulwich College.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) was lodging in Silver Street in the parish in 1604, and the church register for that year records the baptism of his brother's son. It is likely that Shakespeare attended the family ceremony, and during his stay worshipped in the church.

If he did so, he may have met Sir Thomas Lucy (1532 - 1600) who also attended St. Giles when in London from his estate at Charlecote in Warwickshire. It has been thought that Sir Thomas was responsible for Shakespeare's flight from Stratford-on-Avon to London when under threat of prosecution by Sir Thomas for stealing his deer. That would have been an uncomfortable encounter indeed, like some in his plays.

It is also believed that Shakespeare modelled the comic character of Mr. Justice Shallow in The Merry Wives on Sir Thomas Lucy.

Margaret Lucy, his second daughter, who died aged only eighteen in 1634, is buried in St. Giles and her memorial can be seen on the south aisle wall with the touching inscription that to all her friends she was very dear, especially to her old Grandmother, the Lady Constance Lucy'.

ST. GILES DURING THE CIVIL WAR AND THE RESTORATION

Two famous men—one Puritan, the other Royalist— lived close to each other in the Parish. The former was the great epic poet and scholar and ardent supporter of Oliver Cromwell, John Milton. He spent most of his life in the City near St. Giles and was born the son of a wealthy scrivener (solicitor) in Bread Street in 1608. Apart from a brief period from June 1665 to the Spring of the following year when he moved his household from London to escape the plague to Chalfont St. Giles in Buckinghamshire, he lived at various times in Aldersgate Street, Barbican (now Beech Street), Jewin Street, and Artillery Row where he was living when 'Paradise Lost was published in 1667.

He died on the 12 November 1674 and was buried under the chancel floor of St. Giles. His grave is marked by a plain tablet by the steps of the chancel near to the pulpit. His statue, originally standing outside the North door of the church, is now in the South aisle. There is also a monument to him at the West end of the South aisle by the sculptor John Bacon and erected by the famous brewer, Samuel Whitbread in 1793.

The latter,—the Royalist—was Prince Rupert of Bohemia (1619 - 1682) nephew of Charles I, and the famous cavalry leader of the Civil War. After the restoration of his cousin, Charles II, in 1660, he occupied a house at the corner of Whitecross Street and Beech Lane. His last public post was that of First Lord of the Admiralty in 1679. In his later years he confined himself to carrying out scientific experiments in the laboratory that he had built in his house. He was much interested in improving the weapons of war, and invented a method of making gunpowder ten times its normal strength.

It is not recorded whether the two men ever met—a greater contrast between them would be hard to find.

FOUR REMARKABLE VICARS

During the period of the Civil War and its aftermath, St. Giles had four remarkable vicars, each of great strength of character and individuality. They were Royalist, which was unusual in Cromwellian London.

The first, Dr. William Fuller, appointed under Charles I in 1628, was an ardent supporter of the King, He was imprisoned by the House of Commons in 1641 and the living was confiscated by Parliament the following year.

From then until 1658 the Vestry Account Books show that various sums were paid to 'Ministers' for sermons, including a certain Mr. Kelly who preached the Allhallows Day Sermon each year from 1648 to 1658 except for 1649. However, St. Giles appears not to have had a regular incumbent until Richard Cromwell, son of Oliver, appointed Dr. Samuel Annesley as vicar in 1658. His sermons drew large crowds although he was a strong Presbyterian and a Royalist—an unusual combination. In 1661 he published a book of some of his sermons entitled "The Morning Exercise at Cripplegate", and the same year among the many baptisms at which he officiated was that of Daniel Defoe, later to become the famous author of 'Robinson Crusoe'.

His Royalist sympathies, however, did not save him from being ejected from St. Giles the following year—presumably for being a Presbyterian.

He had twenty-five children. His last child, a daughter christened Susannah, married another clergyman, the Rev. Samuel Wesley in 1689 and who later became the Rector of Epworth in Lincolnshire. They had nineteen children, two of whom were John and Charles Wesley, the founders of Methodism.

The successor to the redoubtable Dr. Annesley in 1662 was another man with an equally powerful personality John Dolben, an ardent Royalist who fought for the King in the Civil War. He was wounded at the battle of Marston Moor and again at the siege of York. He only held the living of St. Giles for two years before becoming Dean of Westminster.

It is told of him that during the fire of London, he marched the Westminster schoolboys into the City and kept them hard at work for many hours fetching water. Their efforts resulted in the partial saving of St. Dunstan's in the East from destruction. In the same year he became Bishop of Rochester, and finally in 1683, Archbishop of York, where he died of smallpox in 1685.

The fourth outstanding Vicar of this period was Edward Fowler who faithfully served the Parish for twenty-three years from his appointment in 1682. During his time the Cripplegate Boys and Girls Schools were founded and their early success was largely due to his efforts.

THE PLAGUE AND THE GREAT FIRE

The Parish of St. Giles was the worst affected of any in London by the terrible plague of 1665. It has been suggested that this was due to the parish pump being situated in the churchyard. In the last week of August 600 plague deaths were recorded, and on August 18th there were 151 funerals. 8,000 parishioners died that year, most of them of the plague.

The Churchwardens, the Sexton and the Parish Clerk were amongst those who died. The Vicar was an absentee and the curate at the time Thomas Luckayne ministered to the sick and dying assisted by several nonconformist preachers, some of whom died themselves.

In the Great Fire of September 1666, St. Giles escaped destruction solely due to the City Wall and the width of the churchyard. It was one of the twenty- three churches that survived out of a total of one hundred and twelve in the City before the fire. Today, it is one of the seven pre-fire medieval churches still in existence within the City.

THE RE-BUILDING OF THE TOWER

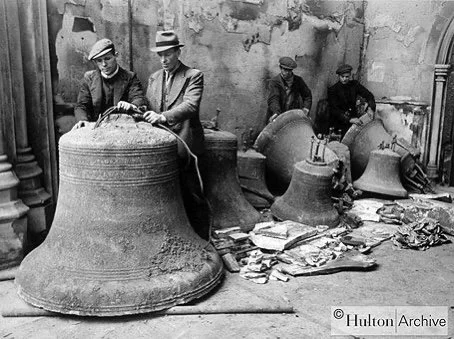

Little further is known about the fabric of the church until 1682 when the tower was heightened by fifteen feet of brickwork to increase the number of bells from eight to a cathedral peal of twelve, and the decayed steeple taken down and replaced by the famous cupola and weather vane.

Apparently, at that time there was a dispute between the Vicar and the Vestry (nowadays the Parochial Church Council) when the Vicar discovered that the Churchwardens had built several houses and shops on land belonging to the Glebe (or Vicar's benefice). A settlement was reached when the Vicar, Edward Fowler, granted a long lease for the land and shops in consideration of the Vestry raising the church tower and re-building the vicarage. However, the Vestry would only build the tower in brick to save expense.

THE SEPARATION OF THE PARISH AND BUILDING OF ST. LUKES

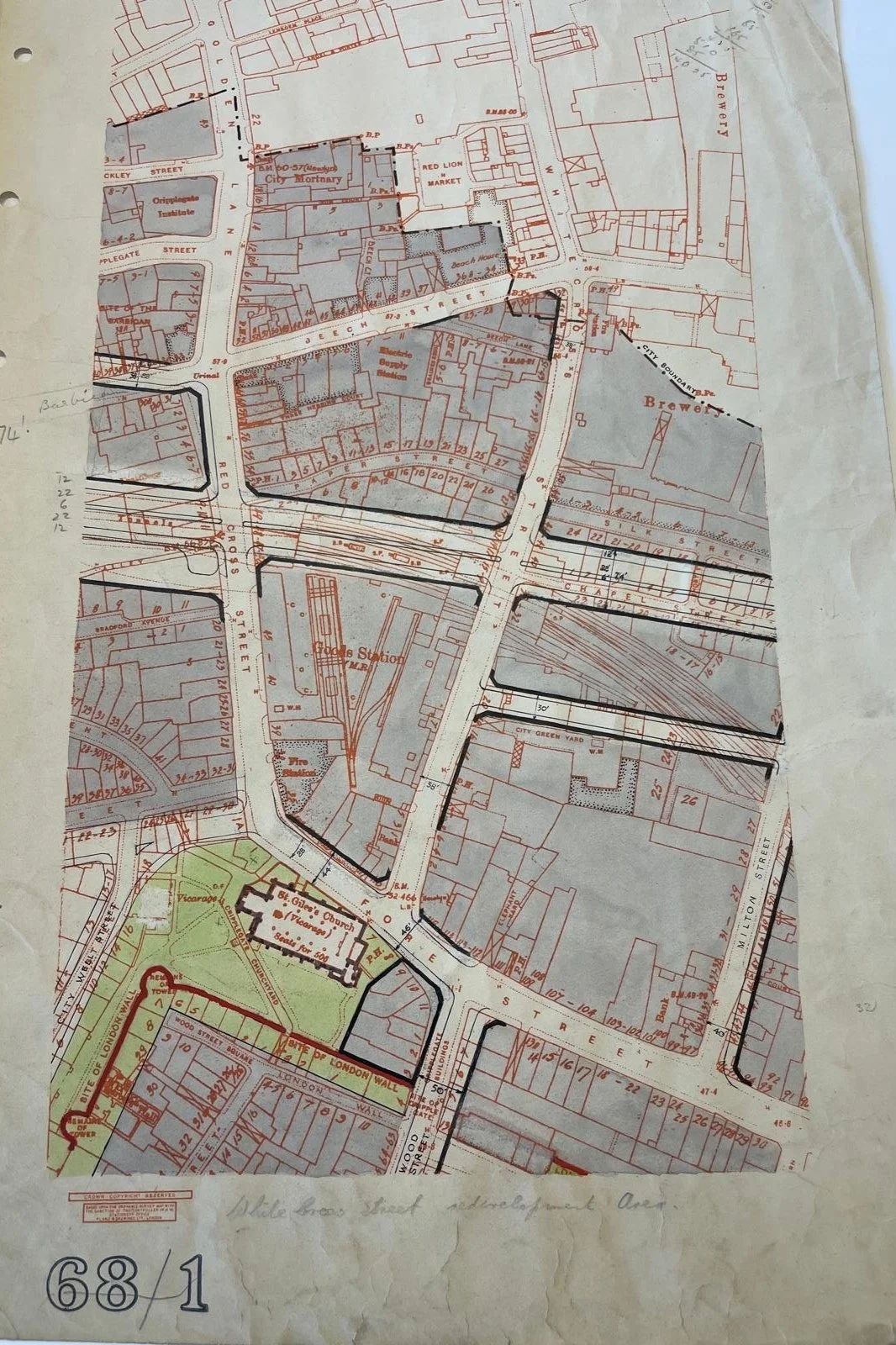

By 1733 the expansion of London after the Great Fire was such that the Lordship or northern part of the Parish was separated from St. Giles and a new church—St. Luke's built on Old Street by the architects Hawkesmoor and John James.

The first Rector of the new church was the Rev. William Nicholls whose restored portrait now hangs in the tower on the south wall.

The newly created Parish of St. Luke's was outside the City boundary and in the years that followed contained some well-known people amongst its parishioners, including John Wesley (1703-1791) the Methodist, William Blake (1757-1827) painter and poet, and David Livingstone (1813 - 1873) missionary and explorer.

RESTORATION WORK ON ST. GILES IN 18th & 19th CENTURIES

The end of the 18th century saw the installation of an oval East window above the high altar (the original window, now reproduced again after bombing, had been bricked up by the building of houses on the East and North sides of the church during the 16th and 17th centuries. At the same time, the pitch of the roof was raised and two additional bays were added to the Clerestory, resulting in the shortened appearance of the east end.

It is highly probable that two parishioners, commemorated by monuments on the walls of the church, played a leading part in the restoration work. The first was the Vestry clerk, Thos. Stagg, attorney at Law, who died in 1772. His monument, at the East end of the south aisle wall near the Vestry door carries the brief inscription 'That is all'. It is now thought that he was a bell ringer besides being Vestry Clerk for the call 'That is all' is said by leading bell ringers at the end of a ringing session.

The second is the colourful figure of Sir William Staines (1731-1807) Lord Mayor of London in 1801 and Alderman of Cripplegate Ward. He was of humble birth from Southwark, apprenticed to a Mason, ran away to sea, was captured by the French, released, returned to his master and completed his apprenticeship. He established a successful mason and builders' business in Cripplegate, and was a well-liked local figure being elected Alderman in 1793. His monument is on the north wall of the church between the font and the north door.

His popularity was such that when chosen as Lord Mayor in 1800, the crowd pulled his state coach from Blackfriars Bridge to Guildhall upon his return to the City after being sworn in at Westminster. The then national hero, Lord Nelson, in London after his victory at the Battle of the Nile, also rode in Sir William's procession.

It is told of Staines that he was fond of his pipe, and when visiting in his carriage, would hand it to his coachman to keep it going for him until his return.

In the latter half of the 19th century major restoration work was carried out. Between 1858 and 1870 the roof and clerestory were renewed with the plastered ceiling to the nave being removed and replaced by a wooden frame inner roof. A new handsome stone chancel arch was substituted for an earlier elliptical plastered one. In 1870 alone, £5,000 was spent, a large sum in those days, and included the restoration of the great West Window in the tower and the north and south aisle windows. As well as other work, a new font was provided.

The churchwarden, John Eddison Claney, who held office between 1865 and 1868 would have been responsible for some of this work. His monument and that of his three wives, Elizabeth, Rosaline and Mary is on the wall in the south aisle just to the right of that of John Speed.

Between 1885 and 1886 the south wall of the church was refaced with Kentish ragstone and the castellated parapet added. Two years later the chancel floor was raised, a new communion table, clergy desks and choir stalls supplied at a cost of £504.18.2d.

In 1890, deterioration was noticed in the upper part of the tower caused by the vibration from the bells. Some members of the Vestry thought that the tower should be restored to its original medieval form by removing the upper fifteen feet of red brick and the wooden cupola and re-instating the tower in stone with a spire to surmount it.

A public outcry ensued, and eventually the 'conservationalists' assisted by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings won the battle to preserve the tower and cupola as they were.

THE CRIPPLEGATE FIRE

Another threat to the brick tower and cupola came on the 29th November 1897, with the outbreak of the great Cripplegate fire. A south-west wind fanned the flames towards St. Giles from burning Warehouses in the neighbourhood. 500 fireman and police fought the blaze, and helped by the Churchwardens and members of the congregation, the church was saved with what damage there was confined to the roof, and with the cupola and pinnacles of the tower blistered by the heat. The repair bill totalled £850, but it was covered by insurance.

However, the vicarage, rebuilt in 1856, and then situated to the west of the church, was badly damaged.

ST. GILES 1900 to 1940

The advent of the 20th century saw a major improvement to the fabric of St. Giles with the demolition upon the expiration of the lease of the Quest House (or Vestry room) and the four shops that had blocked the north wall of the church since 1682.

With the help of donations from the Goldsmiths, Clothworkers and Merchant Taylors' Livery Companies, the north wall was refaced in Kentish ragstone with castellations added to match the south side of the church. The medieval windows were re-instated and filled with stained glass (destroyed in the last war).

The statue of the patron Saint of St. Giles with a hind, situated in the niche over the north door, dates from this time - 1903. The story of St. Giles is lost in antiquity, but it is traditionally supposed that he was a hermit living in a cave on the banks of the River Rhone in Provence in the early 8th century. It is said that he was accidentally shot from the bow of the King of the Goths whilst hunting a hind near the hermit's cave. Legend has it that the King re-visited the hermit who persuaded him to build a monastery. The King only agreed to do so on the condition that St. Giles became its first Abbot. It is also tradition that St. Giles was lame, so in the Middle Ages he became the Patron Saint of cripples and beggars many of whom waited by the principal northern gate of the City. It was therefore appropriate that the church standing without the gate should be named after him. St. Giles Day is September 1st.

The restoration was completed by 1904 and a bronze statue of John Milton by Horace Montford (now in the south aisle) and donated by Sir John Baddeley was placed on a pedestal outside the church, just west of the north door.

Sir John Baddeley was an Alderman of Cripplegate and Lord Mayor of London in 1921 - 1922. His coat of arms is shown on the Lord Mayor's sword rest situated on the nave pillar on the south of the chancel step with those of three other Aldermen of Cripplegate who also held that high office. Не was the author of a detailed history of the City Ward of Cripplegate that is used as a standard work of reference today.

St. Giles escaped damage in the Great War of 1914 - 1918, although the nearby Ironmongers Hall was destroyed in a zeppelin bombing raid.

THE BURNING OF ST. GILES

In the Second World War, the church was not so fortunate. It was the first City church to be a casualty. On 24th August 1940, during a daylight air- raid, a bomb exploded in what was then Fore Street near the north door of the church. However, the damage was not too severe, and it was hoped to complete repairs and re-open the church for Divine Service on New Year's Day 1941.

Unhappily, this was not to be as the church was straddled by incendiary bombs in the Great Fire Raid on the night of December 29th 1940 and completely burnt out. Only the blackened walls and the ruined tower remained. The heat of the fire had been so intense that the stone pillars were calcined. Most of the monuments were destroyed, but fortunately the church registers dating from 1561, the Churchwardens' Account Books from 1648, and the Vestry Minute Book dating from 1659 were rescued and may be inspected at the Guildhall Library.

The church plate and vestments escaped destruction, as, like the records, they were in the Vestry and Muniment Room which survived the fire separated by a wall 4'6" thick from the body of the church. The plate dating from the 17th century is displayed on special occasions such as the Silver Jubilee celebrations in June 1977. Later the Vestry was destroyed by arson, and, after the bombing, the church suffered further desecration from vandalism.

Photographs of the devastated church and the bombed area that surrounded it are shown on the display panels at the west end of the south aisle.

THE RE-BUILDING OF ST. GILES

For nineteen years the church remained in ruins until the slow process of re-construction was undertaken in 1960 supervised by the architect Mr. Godfrey Allen.

The restoration gave the opportunity to re-create the original great 14th century traceried East window, the shape of which had been revealed by the bombing, as the Corporation of London decided to form an open space to the east of the church as part of the new Barbican development scheme.

The beautiful new stained glass window designed and fitted by A.K. Nicholson Studios at a cost of £3,000 was dedicated by the Dean of St. Paul's on 1st November 1967. It depicts famous figures connected with St. Giles set round the Crucifixion which is placed in the centre of the window with St. John on the right, and the Virgin Mary on the left. At the top left light is the patron Saint St. Giles, and opposite on the right St. Paul, since the cathedral chapter are patrons. Above the figure of St. Giles is the Cripplegate, with the crest of the Dean of St. Paul's above that of the Saint. The lower lights from left to right show St. George the patron Saint of England; St. Alphage, Archbishop of Canterbury in the reign of Ethelred the Unready and murdered by the Danes at Greenwich in 1012 A.D. A church was named after him by London Wall whose parish was combined with that of St. Giles after the last war. The ruins of its medieval tower are still preserved. St. Anselm, who was Archbishop of Canterbury in 1090 when Alfune built the Norman church. Bishop Lancelot Andrewes, St. Giles' most famous vicar; and lastly, St. Bartholomew to commemorate the joining in 1902 of the parish of that name with St. Giles when its church in Moor Lane was demolished. Above the figure of the Saint is the coat of arms of the great hospital, whose first hospitaler was Alfune, the builder of the second church of St. Giles. At the very top of the window, above the ten lights, are the emblems of the Passion.

THE RE-UNITING OF ST. LUKE'S WITH ST. GILES

In 1959, due to subsidence, the Georgian church of St. Luke's Old Street had to be demolished; and in 1966 its parish was formally re-united with St. Giles thus ending two hundred and thirty-three years of separation. However, its walls, together with its famous obelisk of a clock tower are still standing on a forlorn sight awaiting improvement.

THE WEST WINDOW

Two years later in 1968, a new stained glass window, showing armourial bearings was installed in the tower by Mr. John Lawson of Faithcraft Studios for the sum of £1,500. St. Giles is shown in its top light, and in the centre of the window is the crest of the City of London with the Arms and Cross of the Archbishop of Canterbury on its left. On its right are the Arms and Staff of the Bishop of London. The five lower lights show the coats of arms of famous parishioners: from the left Robert Glover, Somerset Herald of Arms, John Milton, John Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater, Oliver Cromwell, and Sir Martin Frobisher.

THE BARBICAN DEVELOPMENT

Meanwhile, outside the church and surrounding it, the Corporation of the City of London were building the vast Barbican development scheme with its three 412 ft. high towers to provide high density housing for six thousand people, together with a hostel, and new buildings for the City of London Girls' School and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. The latter forming part of the Barbican Arts Centre with its own concert and conference hall, the new home for the London Symphony Orchestra, a theatre to house the Royal Shakespeare Company and an art gallery and restaurants.

The new landscaping of the area has involved the loss of the old peaceful green churchyard with its many memories, including those of the Great Plague, of which John Stowe wrote in 1598: 'By St. Giles Churchyard was a large water called a Pool. I read in the year 1244 that Anne of Lodburie was drowned therein; this pool is now for the most part stopped up, but the spring is preserved, and was coped with stone by the executors of Richard Whittington' (The Dick Whittington who was three times Lord Mayor of London in 1397, 1406 and 1419).

On the site possibly of the pool mentioned by Stowe, is an imaginatively designed lake filled with goldfish surrounding a brick paved pedestrian precinct from which fine views can be obtained of the restored sections of the old Roman and Medieval City Wall, together with a great bastian previously in the old churchyard, close to the white walled Museum of London.

THE NEW ORGAN

The post-war reconstruction of the church was completed by the installation of the organ in 1968 at a cost of £36,000 including the organ loft. The original organ, a Renatus Harris dated 1704, had been totally destroyed in the bombing; and the new organ built by Mr. Noel Mander, consists of the organ and case taken from St. Luke's Old Street in 1959 and then stored in St. Giles. This organ was originally built by Jordan and Bridge in 1733 for the opening of St. Luke's, and has been combined with two parts of a 1684 Renatus Harris case from St. Andrew's Holborn, with new woodwork for the sides by Architect Mr. Cecil Brown and also for the smaller choir organ projecting from the organ gallery.

IMPROVEMENTS IN THE 1970's

In 1973 a new Communion Altar was provided at the west end of the Chancel to suit the liturgy of the revised Series II and III Sung Eucharist services.

To commemorate the 1977 Silver Jubilee, the restoration of the unusual chiming machine situated in the tower was carried out. It was originally made by George Harman in 1724 - who was a cooper by trade and not a clock- maker. It is able to play a tune for each day of the week on the peel of twelve bells. The tunes are: The Easter Hymn, the National Anthemn, Auld Lang Syne, Hanover, Hark 'tis the Bells, The Mariners' Hymn and, finally, Home, Sweet Home.

The bells can also be rung by hand in the normal manner; and St. Giles tower with its twelve bells is popular amongst groups of bell ringers.

THE CHURCH TODAY

St. Giles is the only parish church within the confines of the City of London that has a residential population of any size approximately 12,000 people now that the Barbican development is complete and including part of South Islington, and it has taken on a new and challenging existence.

The Church is committed to the service of the residential community that surrounds it. In 1976 to expand that work in the northern part of the parish, it opened St. Luke's centre in Roscoe Street, off Old Street, to make good the loss of the old church of St. Luke.

Its work includes chaplaincy work at local schools and hospitals, as well as social work among the handicapped and elderly. It runs active bible study and discussion groups, and has a local drama group linked to it.

St. Giles also serves the local business community and has a weekly lunch hour communion service for City workers as well as being the Ward Church of Cripplegate.